: Could not find asset snippets/file_domain.liquid/assets/img/top/loading.png)

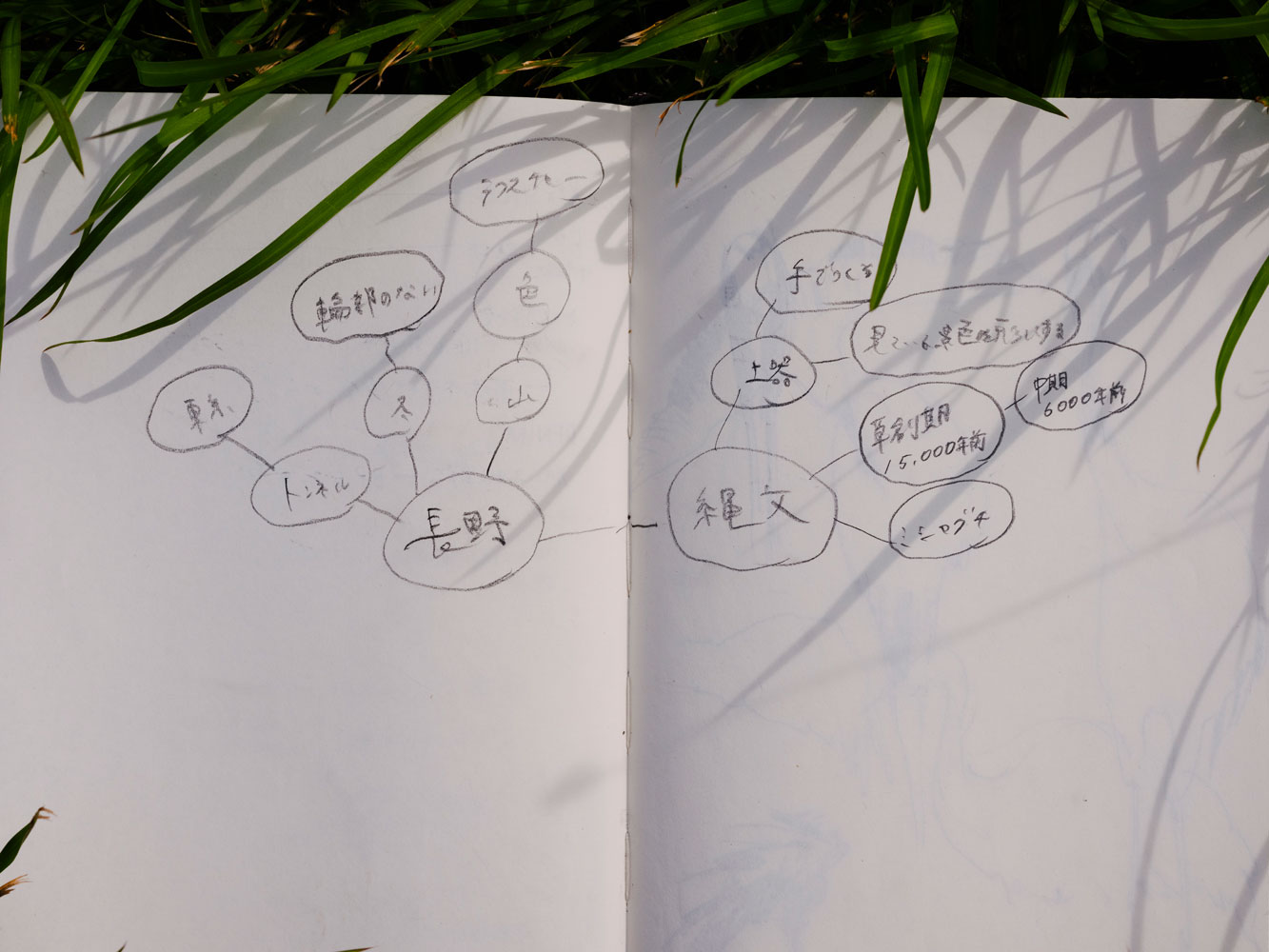

今季のコレクションを司るもっとも重要なインスピレーションのひとつに縄文時代やその時代背景から生まれたさまざまな文化がある。黒河内真衣子は、今から数千年前の縄文時代中期に、自身の故郷がその文化の中心地だったことを知る。縄文時代中期の特異な文化は、なぜ長野から広がっていったのか。そして、そもそも縄文とはどんな時代だったのか。縄文時代や諏訪信仰の研究をする石埜三千穂さんのエッセイと共に紐解いていく。

The Jomon period, as well as the various cultures which emerged from that historical background, serve as one of the most important inspirations for this season's collection. Maiko Kurogouchi learned that her hometown was the center of that culture, thousands of years ago, during the Middle Jomon period. Why did the distinct culture of the Middle Jomon period spread from Nagano? And just what was the Jomon period like? We unravel this story with an essay by Michiho Ishino, a researcher of the Jomon period and Suwa belief.

縄文時代の遺跡は、いまも発見され続けている。しかし、井戸尻遺跡に代表される、呪術的、装飾的な文様をふんだんに盛り込む特有の形式は、いつでもどこでも見られるわけではない。縄文時代中期、千年ほどの期間に限り、八ヶ岳西南麓を中心に、東は伊那谷、南は甲府盆地を経て多摩丘陵、相模の地にまで及ぶ文化圏があった。八ヶ岳東麓の焼町式、松本盆地を中心とする唐草文の土器とも、相互に影響を与え合っている。この特異な形式が生まれてきた背景について、少し考えてみたい。

縄文の図像は、どうして私たちの心に刺さるのだろう。それは言語ではない。そして、アートでもない。しかし、まるで言語のようなコードが存在するのは明らかであり、また、美的感覚にも確実に訴えかけてくる。

コードがある以上、そこには確実に伝えるべきコンテンツがあった。そして複雑な立体文様が刻まれた縄文の甕には、煮炊きの痕跡がある。それは実用品であって、決して鑑賞物ではなかった。

「文明」の成立には、農耕による食料生産、そしてその余剰がなければならないという。「富の蓄積、専有」という話である。もってまわった表現だが、早い話、「所有の概念」こそが文明の始まりであり、経済の始まりということなのだろう。それは残念ながら、組織的戦闘=戦争のもっとも根元的な動機でもある。特に「土地の所有という概念の発明」こそが、人間社会の業の原点だったのかもしれない。

Ruins from the Jomon period continue to be discovered to this day. However, the characteristic form represented by the Idojiri ruins, which incorporates an abundance of magical and decorative patterns, is not commonplace. During the Middle Jomon period, spanning around 1,000 years, there was a cultural region centered at the southwestern foot of Mt. Yatsugatake, extending east to the Inaya Valley, south through the Kofu Basin, all the way to the Tama Hills and the Sagami region. The Yakemachi style pottery from the eastern foot of Yatsugatake, and the arabesque-patterned pottery centered on the Matsumoto Basin, also influence each other. Let us consider for a moment, the background behind the emergence of this peculiar form.

Why does Jomon iconography resonate with us? It is not a language. Nor is it art. However, it is clear that there is a code, almost like a language - and it undoubtedly appeals to the aesthetic sense.

Where there is a code, there is certainly a message to be conveyed. Jomon earthenware, engraved with intricate three-dimensional patterns, shows traces of cooking. It was a practical object, never meant for viewing appreciation.

It is said that to establish "civilization", there must be production of food through agriculture, as well as a surplus of the food produced.

The idea is “the accumulation of wealth, and possession”. This is a roundabout way of saying that the "concept of ownership" is the beginning of civilization, as well as the beginning of economy. Unfortunately, it is also the most fundamental motivation for organized strife, which is to say, war. In particular, the “invention of the concept of land ownership” may have been the origin of business in human society.

縄文文化は文明ではない……と、一般的にはいわれる。それこそが、縄文農耕論を巡る議論の背景だ。木の実を採取し、それを蓄えること。木の実を採取するために特定の植物を住処の周辺で増やそうとすること。

それは農業ではないのか?

いや、「計画栽培」だ!

こうして奇妙な単語が生まれたが、おそらくそれは、「縄文は決して文明ではない」という軸足をブレさせたくないからだろう。イデオロギーの問題なのである。ただ、少なくとも、当たり前に移住を繰り返していた縄文人の生活の中に、「土地の所有という概念」がなかったことだけは断言してよさそうである。(「縄張り意識」くらいは当然あっただろうが)

It is generally said that the Jomon culture was not a civilization. And that is the background to the debate over the theory of Jomon agriculture. Gathering nuts and storing them. Attempting to increase certain plants around their homes, in order to gather nuts.

Is that not agriculture?

No, it is “planned cultivation”!

Thus a bizarre word was born, perhaps in order not to waver from the axis of “Jomon having never been a civilization”. It is a matter of ideology. However, it can be said with certainty that there was no “concept of land ownership” in the daily lives of the Jomon people, who migrated repeatedly as a matter of course. (Although there surely would have been at least a sense of "territoriality")

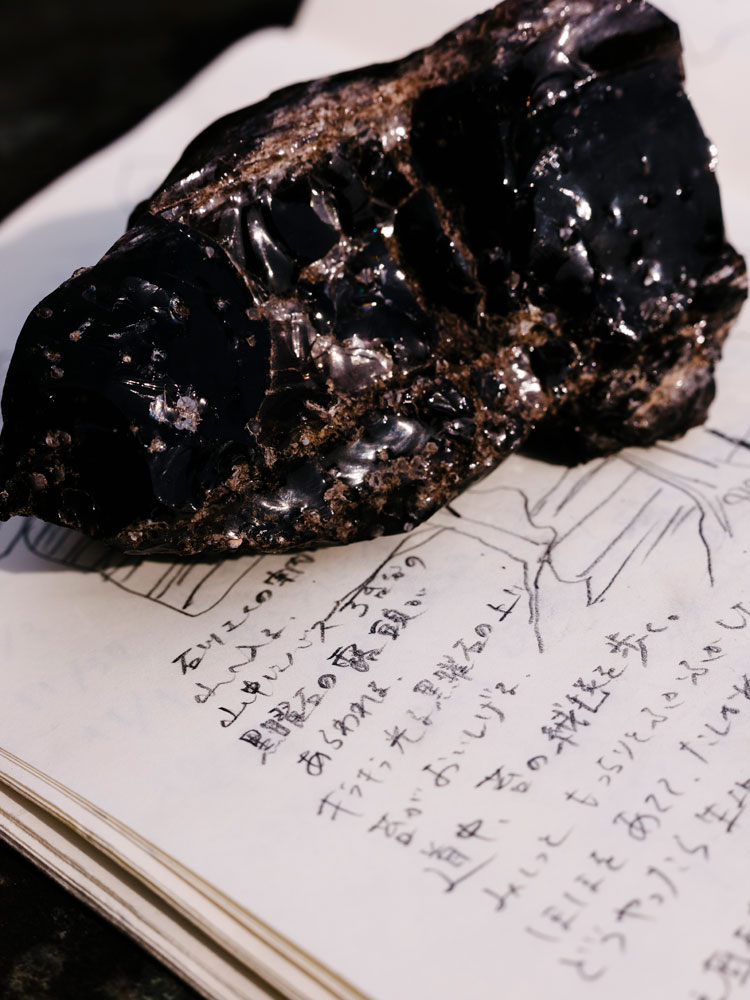

そして縄文人の社会にも道具はあった。いま見つかるのは主に石器と土器だが、もちろん木製の道具もあったし、漆塗り加工の木製品も数多く見つかっている。かつての「原始時代」のイメージとはかけ離れた高文化ぶりである。道具の中でも特に重要なのが黒曜石で、これは鉄器の到来まで、もっとも優れた刃物だった。中でも和田峠周辺の黒曜石は、透き通るブルーブラックで知られ、国内随一の「ブランド」だったといっていい。もちろん、美しいからというだけのブランドではない。刃物として高品質なのだ。

時折、高品質な黒曜石インゴッドの集積遺跡が見つかる。現代人の価値観で、それは「富の集積」に等しいようにも思える。実際、その近辺では比類なく立派な土偶が見つかることが多いのだ。私たちは、そこに「富」の匂いを嗅ぎ取ってしまう。高品質な黒曜石そのものが貨幣のようにすら思えてくる。だが、文明以前のかの時代に「経済」はないのだ。和田峠産の黒曜石は、西は近畿地方、北は北海道でも発見されている。

文明なき時代、経済なき時代に、それはいかにして「流通」したのだろう? 無論、物理的な意味ではない。

Jomon society also had tools. What we find now are mainly stone tools and earthenware, but of course there were also wooden tools, and numerous lacquered wooden products have been found as well. This high culture is a far cry from the common perception of “primitive times”. The most important of the tools was obsidian, the best edged tool until the arrival of ironware. The obsidian around Wadatoge in particular is known for its clear blue-black color, and was once the greatest "brand" in Japan. Of course, it was not seen as a brand just because of beauty. They are blades of superior quality.

Occasionally, ruins are found with an accumulation of high quality obsidian ingots. In the modern person’s perception, this seems to equate to the “accumulation of wealth”. In fact, clay figurines of unmatched splendor are often found in the vicinity. In them, we smell “wealth”. The high-quality obsidian itself begins to feel like currency. However, there is no “economy” in the era before civilization. Obsidian from Wadatoge has been found in the Kinki region to the west, and in Hokkaido to the north. How did it “circulate” in an age without civilization or economy? Not in the physical sense, of course.

私たちの誰にも、ここまで進んできた文明を否定することはできない。やり直そうと思うなら、弥生時代の始まりまで時計の針を戻さなければならない。そんなことは不可能だ。多くの人が現行の文明に行き詰まりを感じ始めているのは確かだが、といって、文明を否定したところでなにも始まりはしない。けれど、文明以前の社会からなにかを学ぶことはできるのかもしれない。

文明以前からのメッセージ。

文明以前の価値観。

それは、決して「野蛮」とか「未開」の一語で片付けられるものではないだろう。

遠い昔からのメッセージを受け取るためには、遠い昔の人々の感じ方、考え方に寄り添う必要がある。思えば私たちは、文明の進歩と足並みを揃え、どれだけ多くの感覚を失ってきたのだろう。極端なことをいえば、便利な道具をひとつ獲得するごとに、感覚をひとつ、引き換えとして失ってきたのだ。

たとえば、時計を持たない時代の人が、空を見上げて時刻を把握する感覚。マニュアル的な技術ではない。おそらく曇天でも、それは機能したことだろう。携帯電話も時計も地図も持たず、どんなふうに待ち合わせをしたのだろう?その待ち合わせ場所まで、私たちは靴を得て、安全に歩くことができるようになった。しかも平坦な舗装の上を。裸足で、草履で、または革一枚のサンダルでも、彼らは地面を歩くだけで、足裏から、また、膝や足首で、さまざまな情報を受け取っていたはずだ。歩くといえば、方位の感覚はおそらく現代人からもっともかけ離れているもののひとつだろう。そして距離感。良し悪しとは別に、感覚がまったく違う。私たちは、「マイカーで5時間かかる」となれば、ちょっと遠いなあと感じる(個人差はおくとして)。しかし近代のはじめころまで、「徒歩で3日」というのは、長旅の範疇ではなかった。そしてどの時代にあっても、実によく遠距離を徒歩で移動していた。当然、時間に対する受容の感覚もまったく違っただろう。こうした人たちのひとりひとりが、現代社会にあってはほとんど超能力者のようなものだ。そんな人たちの「感じ方」を、私たちはどこまでイメージできるのだろう。

長野県は、山深い土地である。峠を越えられる程度の山はまだいいが、北アルプス、南アルプスともなれば完全な障壁となって地域を分断する。千曲川、犀川水系、天龍川。3つの大河がもたらした3つの広大な谷。そして小さなひとつの湖盆。これが長野県を構成する主だった環境といえる。

それぞれの地域は山地で隔てられ、無数の峠で結ばれる。勢い、交通の要衝、ターミナルとなる場所も自然に定まってくる。そして、山地のただ中にも、人は住む。不便だと思うのは現代人の感覚で、山中は資源豊富で水害が少ない(山崩れするような場所は避ける知見もあった)。豊かに暮らし、健脚を伸ばして日常的に町まで行き来していたのだ。

長野県という土地に特異性があるとしたら、この非連続性と連続性とのバランスが生み出したものなのかもしれない。八ヶ岳山麓で富士山の噴煙を眺めていた縄文人たちも、さまざまな目的でその健脚を伸ばしていたことだろう。大きな目的があればより遠くに。小さな目的ならば峠を越えることもない。そうして文化の伝播の偏差が生まれていく。

縄文中期の八ヶ岳山麓のように。

善光寺のように。

諏訪大社のように。

峠を越えてきたものが吹き溜まって坩堝となり、拠点となり、その影響はまた峠を越えていく。文明は社会の仕組みを人間の手でつくっていくものだ。科学と合理の上に、それは成り立っている。そして思想や信仰は、人間が世界の仕組みを把握しようとするものだ。移動し、留まり、考えて、伝えながら。

千年間、不可思議な文様を生み出し続けた人々は、世界をどのように捉えていたのだろう。ともに生きる動物や植物に対して、どんな思いを抱いていたのだろう。山に、河に、海に、空に、太陽に、月に、星に対して、どんな思いを?縄文人の「言語らしきもの」を完全に解読することは、おそらく不可能だろう。それでも、躍動する文様を眺めて。交錯するコードを凝視して。私たちは、なにを、どこまで、イメージできるのだろうか?

None of us can deny a civilization that has advanced this far. If we want to start over, we would have to wind the clock back to the beginning of the Yayoi period. But that is impossible. Certainly, many people are beginning to feel that the current civilization has reached an impasse, though, nothing is born through the denial of civilization. However, perhaps there is something to be learned from pre-civilization societies.

A message from before civilization.

Pre-civilizational values.

This will never be something that can be reduced to words like “barbaric” or “uncivilized”.

In order to receive a message from the distant past, we must try to understand how people from the distant past felt and thought. Thinking back, how many of our senses have we lost in keeping pace with the progress of civilization? We could even go as far as saying that, for every useful tool we have acquired, we have lost one of our senses in exchange.

For example, the sense that people had in the era without clocks, of looking up at the sky to keep track of time. That is not a skill that goes by any manual. It would surely have functioned even on cloudy days. How did they meet up without cell phones, watches, or maps? We have acquired shoes, and become able to walk safely to our meeting places. And on flat pavement, that is. Whether barefoot, in zori (Japanese straw sandals), or in sandals made from a single piece of leather, they would have received a variety of information from their feet, knees, and ankles, just by walking on the ground. On the subject of walking, the sense of direction is perhaps one of the most detached for the modern person. And a sense of distance. Beyond good or bad, our senses are completely different. If it “takes 5 hours by car”, we feel that it’s a little far (leaving aside individual differences). Until the beginning of the modern age, however, "three days on foot" was not considered a long journey. And in any era, people were indeed often traveling long distances on foot. Naturally, their sense of acceptance towards time would have been completely different.

Every single one of these people would be practically like a psychic in today's society. To what extent can we imagine the “perception” of such people?

Nagano Prefecture is a mountainous area. While mountains that can be crossed by passes are fine, the Northern and Southern Alps are complete barriers that divide the region. The Chikuma river, Saigawa water system, and Tenryu river. Three vast valleys, caused by three great rivers. And a single, small, lake basin. This is the main environment that forms Nagano Prefecture. Each region is separated by mountainous terrain, and connected by countless mountain passes. Momentum, strategic regions for transportation, and terminal locations are established naturally. And even in the midst of mountainous terrain, people live. It is only inconvenient through the perception of modern people, since mountains are rich in resources and less prone to flooding (there was also the knowledge to avoid places where landslides could occur). They lived a life of plenty, traveling to and from town on a daily basis.

If there is any unique quality to the land of Nagano Prefecture, it may have been generated by this balance between discontinuity and continuity.

The Jomon people, watching Fuji's plumes of smoke from the foot of Mt. Yatsugatake, must have traveled for a variety of reasons. Farther for a greater purpose. For lesser purposes, not even crossing the mountain pass. And so, deviations in culture diffusion arise.

Like the foot of Mt. Yatsugatake in the Middle Jomon period.

Like Zenkoji Temple.

Like Suwa-taisha Shrine.

What comes through the pass settles into a melting pot, a base, from which those influences cross the pass once again.

Civilization is the creation of a social structure by human hands. It is built upon science and reason.

And thought and faith are attempts by humans, to grasp how the world works.

While moving, staying, thinking, and communicating. These people who created mysterious patterns for a thousand years - how did they perceive the world? How did they feel about the animals and plants they coexisted with? What did they feel towards the mountains, the rivers, the sea, the sky, the sun, the moon, and the stars? Without a doubt, it is impossible to decipher completely the "language-like" code of the Jomon people. But even so, seeing the dynamic patterns. Staring at the intersecting codes. What, and how far, can we imagine?

Photography: Masaru Tatsuki/ Words: Michiho Ishino/ Edit: Runa Anzai (kontakt)