: Could not find asset snippets/file_domain.liquid/assets/img/top/loading.png)

「かたち」からコレクションをつくろうと思ったとき、真っ先に頭に浮かんだのは沖縄だった。

恐らく、以前訪れた際に伝え聞いた三日月のような爪の紋様の生地の話が、ずっと頭の片隅に残っていたからかもしれない。日常が図案となり、織物や染め物、工芸品へと姿を変えていく。それがあまりに自然で、もう一度その景色を見てみたいと思った。数年ぶりに訪れたその地で、私はやはりもう一度心を奪われた。

琉球王国を代表する美のひとつに漆器がある。貝殻を切り出して貼り付ける煌びやかな螺鈿や、立体的な柄表現を可能にする堆錦といった華やかな技法によって、漆器は琉球の外交において重宝され、交易とともに発展を遂げる。しかし、その後に訪れる明治維新と戦争が、芸術にも苦難を強いる。沖縄の美術館には、日中・日露戦争前後にお土産品として作られた漆器が展示され、その時代の名残を留めていた。その後、幾星霜を経て今もなお、琉球漆器は現代の人々の暮らしに寄り添っている。

付箋だらけの『日本のかたち』の中の1ページに、可憐な小花が描かれた漆器が佇んでいる。美術館で目にした古い琉球漆器は、川の流れや佇む草花で彩られていて、琉球の豊かな大地の記憶を宿していた。艶やかに光を湛える漆の漆黒に吸い込まれた私は、いつしか私なりの花鳥風月をその黒に浮かべてみたいと思っていた。

深く、底の見えないほどの漆の黒さを生地で表現してくれた群馬県桐生市の機屋は、普段はネクタイ地を得意としている。経糸・緯糸ともに1cmあたり100本近くの糸をかけた高密度の織物の上を、小鳥が艶やかに舞い、せせらぎが作る水紋の脇には、可憐に咲く草花たちが踊る。

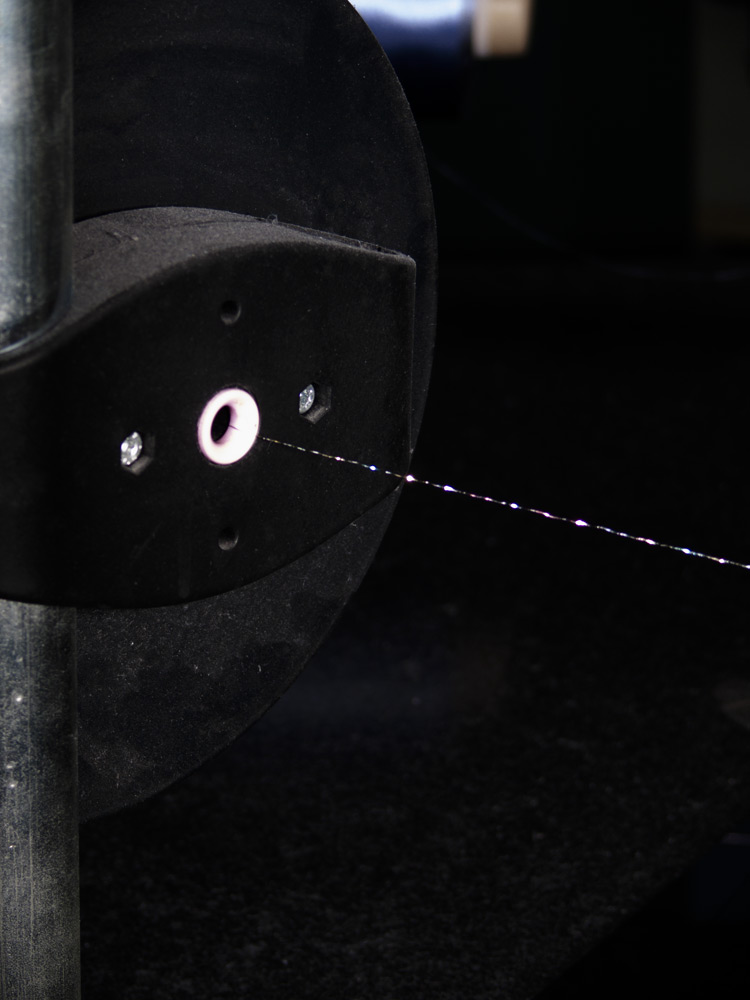

さまざまな箔糸を試し、試作を重ね、白と黒、2色の生地それぞれに最も美しく光を湛える糸を選び出し、織り込んだ。螺鈿のようなオーロラの輝きが私の景色のかたちに命を吹き込んでくれる。生地の裏側には虹色の糸が無数に、流れるように渡り、光を孕んで一層美しい。仕立ててしまえば表からは見えないけれど、見える景色が全てではない。

細かな図案は墨で描いた。何度も余白を見つめ直し、筆をとっては、また置いた。漆黒の漆の美しさを際立たせるには、間の取り方がすべてなのだから。

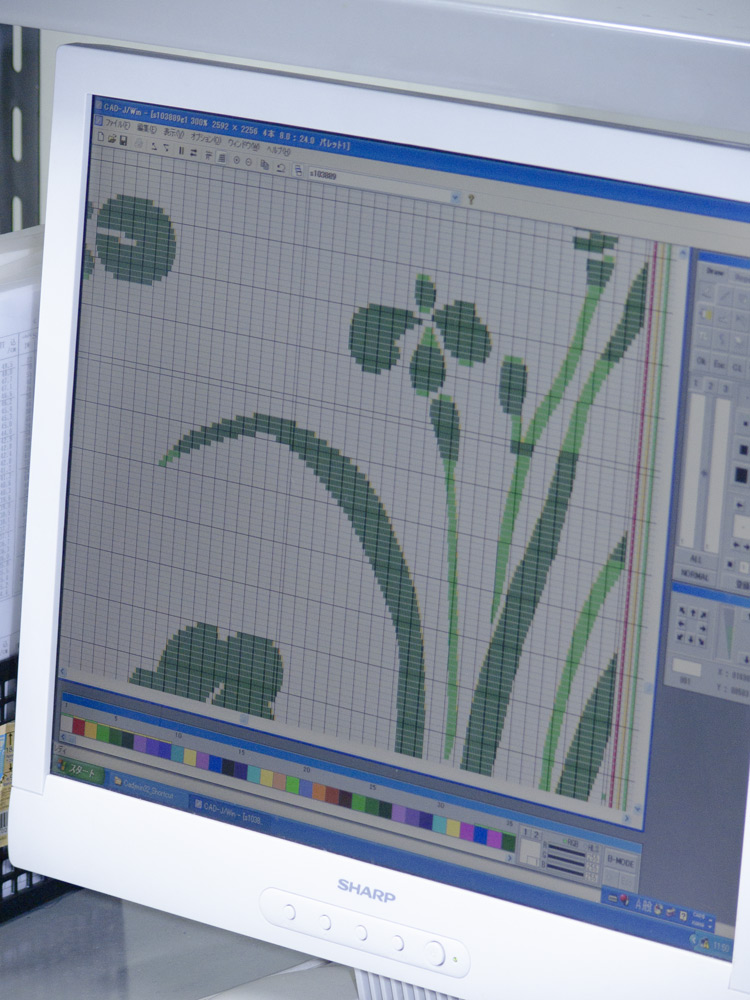

生地図案のデータ化を担ってくださる方々もまた、私の手描きの揺らぎをじっと見つめ、意図せぬその線を損なわぬよう、わずかな歪みまで丁寧に残してくださる。それは、1ピクセルごとに調整を施す、気の遠くなるような作業だ。そうしてデータ化された私の景色は、その後も試織を繰り返し、時間をかけて育てられていく。

When I first conceived the idea of creating a collection inspired by "form," Okinawa was the very first place that came to mind.

Perhaps it was because a story I had once heard lingered in the recesses of my memory—a tale of fabric adorned with crescent-moon-shaped claw motifs. The everyday becomes design, which in turn transforms into textiles, dyed fabrics, and exquisite crafts. This seamless evolution felt so profoundly natural that I longed to witness it once more. And so, after several years, I returned to that land, only to find myself once again utterly captivated.

Among the many expressions of beauty that flourished in the Ryukyu Kingdom, lacquerware holds a special place. Adorned with radiant mother-of-pearl inlays, meticulously cut and set into the surface, or embellished with the intricate, raised patterns of tsuikin (moulded decoration), Ryukyuan lacquerware thrived as a treasured artefact of deplomacy. As commerce flourished, so too did its artistry. Yet, history did not let it thrive. The Meiji Restoration and the devastation of the pacific war cast their shadows upon these crafts, forcing even art itself to endure hardship.

In an Okinawa’s museum, wartime lacquerware—created as souvenirs during the conflict—serves as a poignant reminder of those turbulent times. And yet, through the passage of countless seasons, Ryukyuan lacquerware continues to weave itself into the fabric of modern life, its luminous beauty quietly standing the test of time.

On a page in The Shape of Japan, covered with sticky notes, there rests a lacquerware piece adorned with delicate flowers. The ancient Ryukyu lacquerware I encountered in the museum was painted with flowing rivers and still flowers, holding within it the memory of the rich land of Ryukyu. Drawn into the glossy, jet-black lacquer, I found myself yearning to imprint my own vision of the Four Seasons in that same black.

The weaver from Kiryu City in Gunma Prefecture, who expressed the deep, unfathomable black of lacquer through fabric, is typically known for their expertise in necktie fabrics. On the high-density weave, with nearly 100 threads per centimetre in both the warp and weft, little birds flit gracefully, and beside the ripples of a babbling brook, flowers bloom in an elegant dance.

After experimenting with various foil threads and numerous prototypes, I carefully selected the threads that best captured the light in both white and black fabrics. These threads were woven into the fabric, their colours shimmering like the luminous iridescence of mother-of-pearl, breathing life into the shape of my vision. On the reverse side of the fabric, countless rainbow threads flow in a delicate stream, carrying light and becoming even more beautiful. Though hidden once made into garments, not all beauty is visible in what can be seen.

The intricate designs were drawn with ink. I repeatedly revisited the empty spaces, taking up the brush, then setting it down again. To bring out the true beauty of the lacquer black, the spacing between elements was everything.

Those who helped digitise the fabric designs also carefully studied the subtle wavering of my hand-drawn lines, ensuring that no unintentional strokes were lost, preserving even the tiniest distortion. This was an endlessly meticulous process, adjusting pixel by pixel. The digitised version of my landscape was then refined through repeated sample weavings, gradually nurtured over time.

生地の上に小さな蝶を飛ばしたのは、沖縄で聞いた紅型職人の話がきっかけだった。完成した生地を干していると、蝶が舞い降り、花粉を落としてしまうことがある。そうすると、その生地は不良品となってしまう。しかし、それを見たあるお客様は「世界に一点しかないものだから」と、その生地を望んだという。

その話を聞いたとき、私は沖縄の青々とした空をひらひらと舞う蝶を想像した。その情景を、思い出としてここに残したいと思った。

The inspiration to scatter small butterflies across the fabric came from a story I heard from a Bingata artisan in Okinawa. When the finished fabric is hung out to dry, butterflies sometimes land on it, dropping pollen. As a result, the fabric is deemed defective. However, one customer, upon witnessing this, desired the fabric, saying, "It's one of a kind in the world."

When I heard this story, I imagined the butterflies fluttering against Okinawa's vibrant blue sky. I wanted to capture that scene, preserving it here as a memory.